Complete Symphonies and Dances

National Symphony Orchestra of Ireland

Queensland Symphony Orchestra

Andrew Penny conductor

Naxos: 8.506041 (6 discs)

In the early nineties record companies began to invest in recordings of music by Sir Malcolm Arnold. No fewer than three – Chandos, Conifer and Naxos, began cycles of all the symphonies. It is the Naxos set along with a complete recording of his British dances that is reissued in this beautifully packaged budget price box.

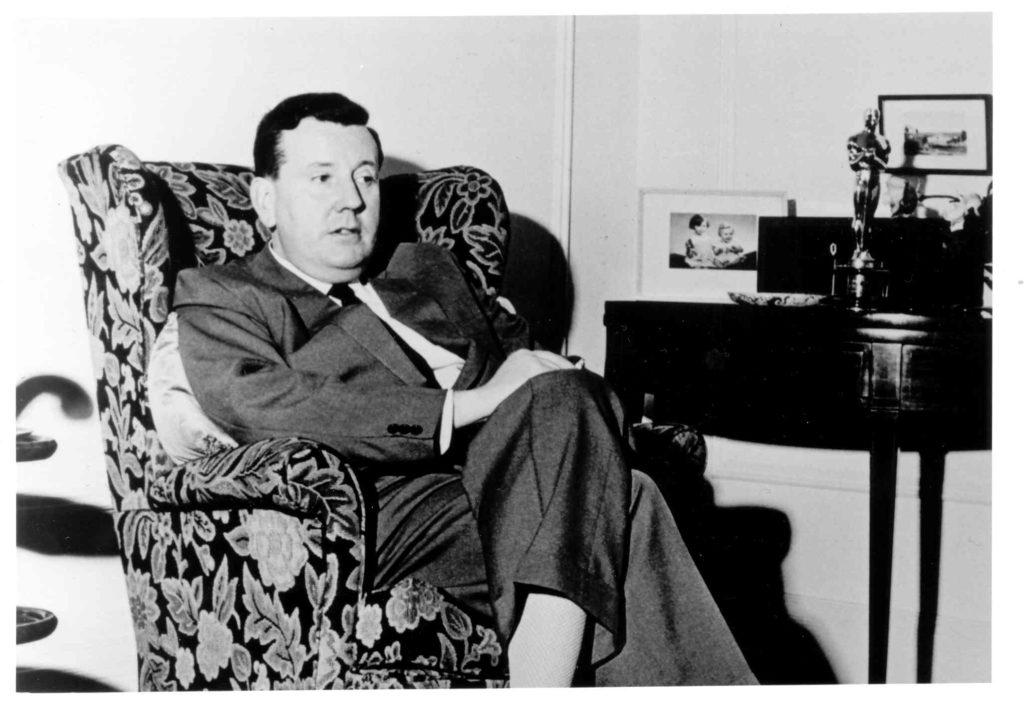

Andrew Penny is a wonderful conductor, with a real feel for Arnold’s music and well up to the technical demands in conducting them. He should be better known but has, for some reason, sadly disappeared from view in the last 15 years, although he does write an introduction for the liner notes.

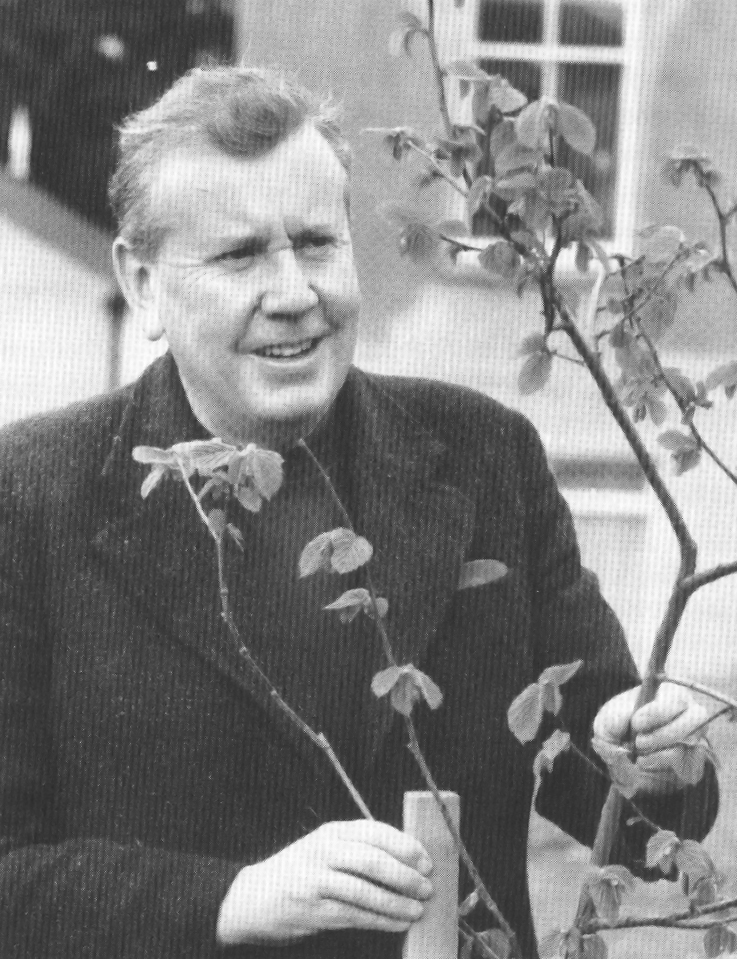

What we have here are the nine numbered symphonies, though sadly not the string symphony, brass symphony or toy symphony. The composer attended all the recording sessions over a period of five years, which must have been both a blessing and a curse.

Before I go onto the symphonies, I will mention that the box also includes excellent recordings of all of the national dances which were the beginning of his fame and his downfall. The English, Scottish and Cornish sets became so popular that they overshadowed his more ‘serious’ writing.

The 20th century was not the 19th so how could a composer possibly write quality, appealing music? Surely it must be cheap? The jibe stuck. This is not the place to discuss ‘light music’, but the Arnold dance suites are not ‘light music’ as the term has come to be used.

If you want to listen to the difference listen to Iain Hamilton’s Scottish Dances, which are light music and then compare them to Arnold’s, there is an audible and emotional difference. The first set of English Dances from 1950 were the brilliant idea of his publisher Lengnick and were to be latter day versions of Dvorak’s Slavonic Dances, which Lengnick also published.

They were hugely popular, and the second set appeared a year later. They have never been out of the repertory of pops concerts around the world, and they are beauties. No actual folk tunes are used but Arnold has conjured up music which by his use of intervals and modes is perceived as quintessentially English.

The orchestration is immaculate, not a note or instrument out of place and here the players rise to the challenge of the many difficult solo passages. I say ‘immaculate’ but having played it, the tuba solo in No 4 is in an awkward place for the instrument to sound at its best.

The Scottish Dances do use a tune by Rabbie Burns, but the energy of the orchestration is pure Arnold. The orchestra brilliantly imitate the drone of the bagpipes and he doesn’t overdo the humour of the drunken bassoon in number 2. Play what is written and the joke is there, it needs no tomfoolery.

The trumpet glissandi in the final fling have never sounded better. To call the Cornish set ‘Dances’ is stretching the point, they are more Cornish portraits, but the name has stuck. Mr. Penny’s first dance could have more drive, but the Moody and Sankey hymn of dance 3 is played perfectly and as, instructed, senza parodia. The Irish and Welsh Dances from the 80s are not in the same league as the previous sets, though both orchestra and conductor give them their best.

The symphonies are paired chronologically with No. 9 occupying a single disc alongside an interview with Sir Malcolm at his most laconic. As the parings show no two symphonies are alike and they chart Arnold’s compositional development and also the enormous problems he faced in his life.

Nos 1, 3, 6, 7and 8 have three movements, 2,4,5 and 9 have the more traditional four, but no matter how many movements, they are packed full of the most powerful and personal utterances Arnold ever wrote. He said, ‘all of my music is autobiographical’, and the symphonies are the backbone of his compositional life.

Most were written at times of emotional turmoil, and they express his deepest feelings. If the dances are mostly light (though they are not, as noted above, light music), the symphonies are mostly dark, although he usually tried to end on a positive note; only symphonies 5 and 9 end quietly.

Symphony No. 1 is from 1949 though it had to wait until 1951 for its premiere. It is a strong work for a young composer. We can hear Arnold flexing his compositional muscles; tightly developed rhythmic cells, broad melodies, impeccable orchestration, widely contrasting dynamics, from sweet little phrases to violent outbursts; all are Arnold and yes, it is disturbing music.

It is a tough symphony to bring off as much of the fragmentary material in the first movement does not have a forward motion, and it can seem to be stopping and starting. Mr. Penny just keeps that in check and the orchestra are superb. The solo entries in the finale’s fugue are stunning. The sudden brief appearance of the daft march tune is as shocking as it should be, and as he intended, we are left thinking “why?”

Symphony No. 2 was for many years Arnold’s most popular symphony, and in its first year, 1953, it had numerous international performances. That is understandable as it is the sunniest of his symphonies. The finest recording is undoubtedly that by Sir Charles Groves, who premièred the work, but Mr. Penny and the Irish orchestra come close, though a slight thinness of string tone just holds the recording back from being first rate. The fleetfooted Scherzo is beautifully judged and the great peroration in the finale, which is sometimes played too slowly and sounds overblown, is here perfectly in proportion to the rest of the work.

Symphony No. 3, premiered in 1957 was written in memory of his mother and is understandably a darker work. The long, desolate, central passacaglia is beautifully shaped by Mr. Penny, who wracks up the tension unbearably. This central movement is flanked by two wildly contrasting ones. The first movement’s bleak Sibelian opening melody is contrasted with a rapid passage in thirds in which the wind and brass need to be on top form to keep up.

I have heard performances where one was worried for the safety of the trombones, but here the Irish players make light of its technical challenges. After two such weighty movements it is tough for the conductor to bring off the lighthearted finale, without it seeming like an add on, but once again Mr Penny is more than up to the task, the skittish material held well under control, and as in his approach to No. 2, the final peroration is natural and not forced.

Arnold’s real problems with the critics began in earnest with his 4th Symphony from 1960. They simply could not understand that a symphony which incorporated so many musical styles could be serious. At the time Mahler was not really popular, and likewise Shostakovich was barely known. With hindsight we can see Arnold’s work as forward thinking, but at the time it was panned. Inspired in part by the Notting Hill Race Riots, the symphony incorporates important parts for Caribbean inspired percussion, bongos, tom-toms and unusually for him, marimba.

In the first movement these instruments are contrasted with a seemingly facile English tune that would not be out of place in documentary on Sussex. The violent interaction between these two ideas, which can seem alien to one another, is carefully handled by Mr Penny. The percussionists also show their métier in the dynamic fugal finale, where their statement of the fugue is tightly shaped in both rhythm and phrasing. Nothing beats Richard Hickox’s profound and stunning recording with the LSO, but these players come close.

By the time of Symphony 5 a year later the critics really had the knives out for the composer, and in their calumny really missed the enormous skill with which the symphony is constructed. It is largely a memorial to dead friends including Gerard Hoffnung (tuba), Dennis Brain (horn) and dancer David Paltenghi (clarinet). But it also incorporates into its musical material the initials G.A. H. for Hoffnung and his wife, H being B natural in German notation.

The serial framework of the first movement is interrupted often by the glitteringly tonal Hoffnung theme played in close cannon on harp and glockenspiel. The horn, clarinet and tuba soli are all beautifully played, though the shaping of the movement misses out on the profound sadness that Arnold’s own with the CBSO brings to the work.

The Hollywood-like slow movement whose seeming sentimentality caused the early critics so many problems, is here not maudlin but luminous, though maybe the celeste player’s arpeggios are not quite in time. In the finale Mr Penny, wisely, again, does not wallow over the return of the ‘big tune’, and in so doing makes it bleak ending all the more understandable.

Symphony No. 6 was written in Cornwall and premiered in 1968, at what was the beginning of a very difficult time personally for Arnold. He was out of favour with critics and the BBC, and his second marriage was in trouble, stress having been placed on it by his drinking, and the birth of a second son Edward, who was diagnosed as autistic.

Although Arnold told me that ‘Edward’s birth caused me great anguish. Though I love him more than life itself’, these events influenced the symphony, and it is a stormy, unsettling piece. Add into the mix a homage to Charlie Parker’s style of jazz and some current pop trends and one can see it is a daunting work to bring off. Once again though, Mr Penny and the orchestra rise to the challenges, matching content to form and it is a tightly shaped performance, with some wonderful dynamic contrasts.

The piccolo player must be singled out for spirited playing of the Parker style jazz, something they cannot be called upon to do every day. The slow movement is positively Ivesian in its stagnant harmonies which are interrupted only by the afore-mentioned pop tune complete with pulsing tambourine. It is a deeply unsettling movement from which Mr Penny draws every moment of pathos. Like Symphony 3, the rondo finale is in brilliant contrast to the other two movements. The clouds are swept away by a forward thrusting tune and, with bells sounding out, the work ends in a blaze of, perhaps, forced optimism. The sound engineers capture the full sound beautifully.

The only optimism in Symphony No. 7 (1973) comes from a very large cowbell which Arnold said signified hope. But it appears seldom, and hope is only a glimmer in this Arnold’s darkest utterance. Written when his personal life was falling apart, and mostly at the Walton’s home on Ischia – I say ‘mostly’ because they ultimately asked him to leave as his behavior became intolerable – the work is a none too flattering portrait of his children and wives.

This is not my imagination, Arnold did say this and when, in 1998 I found the sketches in his attic, it was clear he had gone to great lengths to use their names as musical cyphers, much like the initials BACH or DSCH, have been used. So, the violent angry opening is based on the names of his children Katherine, Robert and Edward, all jostling to be heard, while a dissonant chordal passage is the names of his wives, Sheila and Isobel plus Katherine, played on top of each other.

This is however a dystopian world that says more of Arnold’s fragile mental state than a real picture of his family. The violent first movement is Katherine, the second Robert and the third Edward. The most extraordinary movement is number two where Robert Arnold, who had been seriously ill while in Micronesia, is portrayed.

The extraordinary trombone solo, here nobly played, and the use of multiple percussion conjures up a chilling fearful world. The finale has some light where Edward Arnold’s love of the Irish band The Chieftains is put to use by incorporating quasi-Irish folk music. In live performance this work is overwhelming in its emotional punch and some of that power is captured here.

Symphony No. 8 (1978) is all smoke and mirrors. Written while his aged father was rapidly declining, all is not what it seems. It is incredible that he was able to fulfil his commission – for the Albany Symphony Orchestra in New York State – at all, as two suicide attempts had left him in both physically and emotionally in a dreadful state. Much of the work was written in the difficult surroundings of London’s Royal Free Hospital.

An explosive, dissonant fanfare leads into a simple folk like melody, but listen closer and the strings hold a quiet A flat while the piccolo melody is in D major, the interval of the tritone, the diabolus in musica. Add to that, that the tune is from The Reckoning his final film score, in which a man confronts the death of his estranged father, and the layers of meaning become more complex.

Every time the tune reappears it is attacked more forcibly by the orchestra. There are some stunningly original moments of orchestration, a tuba duetting with a horn, a vibraphone with timpani, acoustically gorgeous and perfectly captured here. Arnold was very good at metronome- marking his scores, but in the brilliant finale to No 8 something went awry, and an editor should have stepped in. He marks it Vivace, crotchet = 160, a speed no conductor takes and a speed at which the accelerando into the final pages would be almost impossible.

Handley on Conifer takes it at 152, Gamba on Chandos 144, and here Penny opts for 132. Mr Penny’s speed is too pedestrian to capture the movement’s excitement, while Mr Gamba (who was brought in to complete the cycle for Chandos after Richard Hickox’s untimely death) seems to me to get it exactly right. This is Mr. Penny’s only miscalculation in an otherwise beautifully paced interpretation.

Symphony No. 9, as I wrote in an earlier review, is a tough work. At the end of his compositional life the symphony is his music stripped to its bare bones. The glorious melodies are still there but the rhythmic cells which are such a part of his compositional style here become hermetically sealed. But in this perfectly paced reading, Penny finds heart aching beauty in the simplicity.

In the very long, very slow finale and we realise that, as Arnold said to me, ‘I wrote what I meant, and not a note is out of place. Stunningly difficult to bring off, the glacial pace is essential to this movement’s integrity and Mr. Penny has the technique and the belief in Arnold’s writing to keep the whole extraordinary structure together. The slivers of hope in the brief trumpet and horn fanfares are tear jerking. It is deeply moving and deeply sad, pathetic in its truest sense. But, with the final radiantly scored D major chord there is a possibility of hope.

This was, in 1996, the first and as yet unsurpassed recording of the ninth. Mr Penny and his orchestra believe wholeheartedly in it. The filler interview with Arnold and Penny, has been heavily edited and is difficult, heartbreaking even, like most interviews with Arnold were in his final years.

The decades of appalling treatments for his schizophrenia and alcoholism had taken their toll and here he was showing the signs of the dementia he suffered in his final years. But Penny perseveres and it shows Arnold’s respect for the conductor that some of the answers are meaningful.

Many ideas have been put forward over the years as to why Arnold’s symphonies have not entered the standard repertoire. He is a film composer, incapable of symphonic thought? He was out of touch with current trends? Audiences do not want to hear him? Patently not true, as when the BBCSO under Sakari Oramo played No 5 at this year’s Proms there was rapturous applause, and the conductor held the score high above his head in triumph.

Richard Morrison of The Times was the lone voice still berating Arnold. But in this his centenary year not a single London orchestra, not even his old orchestra the London Philharmonic, have programmed a single work by him, let alone a symphony.

The LSO who magnificently recorded symphonies 1-6 only, programmed one public performance, that of No. 5, when Mr Hickox conducted it at a 75th birthday concert. I can only hope that all concert producers realise the error of their ways, for as this set shows these are major works by a major composer just waiting to take their place amongst the symphonic canon.

Review by Paul RW Jackson