PAUL SPICER

Robert Hale/Crowood Press

It seems quite extraordinary that it has taken almost half a century since his death for a biography of such a significant figure as Sir Arthur Bliss to appear. As composer, conductor, writer, and administrator he was central to the musical life of the UK over 50 years. As Master of the Queen’s Musick (he liked the old spelling) he created some of the greatest ceremonial music ever written, and used his position to promote music and musicians wherever he could. Following his death in 1975 the importance of the post has withered away to almost insignificance. Apart from rare occasions, his music has seldom appeared on concert programmes.

Mr Spicer is a distinguished musician, particularly in the field of choral music, and he has written well-received biographies of Herbert Howells, with whom he studied, and Sir George Dyson. He observes in his preface that when asked to write this book he realised he knew very little of either Bliss the man or his music. He decided to go ahead with a clean slate, interested as to what he might find. Bliss said he often needed a trouvaille to begin a work and Mr Spicer has also found one in a comment from Bliss – that to know him we need to listen to his music. This probably accounts for the particular focus on the music rather than the man.

In writing the book Mr Spicer had a good starting point in Bliss’s hugely enjoyable autobiography As I Remember, which took his life up to 75 and which appeared in 1970. This was updated for his centenary by his widow Trudy, who died in 2008 aged 104. She donated much of his correspondence to his alma mater Cambridge University, where it can be found beautifully catalogued. From these useful starting points Mr Spicer has constructed a straightforward chronological timeline from cradle to grave.

He is at his best in surveying the music, which is clear and understandable to anyone with a basic level of musical knowledge. Some of it is not flattering, and he spends a number of pages discussing the opera The Olympians, before telling us, in no uncertain terms, he does not think it worth reviving. The film music is well covered and there is a surprising amount of it, far more than the classic Things to Come (1935). That film and the composer’s relationship to H.G. Wells is one of the strongest parts of the book. Likewise, the ballet music is well served. Sadly, the highlighting the enormous success the first three enjoyed at their premières, only serves to show how sad it is that they are so rarely performed these days, either on-stage or in concert.

It is clear that Bliss was nothing if not resilient, and he did have a number of major setbacks in his career. The Beatitudes, for example, was written for Coventry Cathedral, but was unceremoniously moved out of that venue to one far less suitable, to make way for Britten’s War Requiem. Bliss took it all in his stride and never let the event interfere with his cordial relationship with Britten.

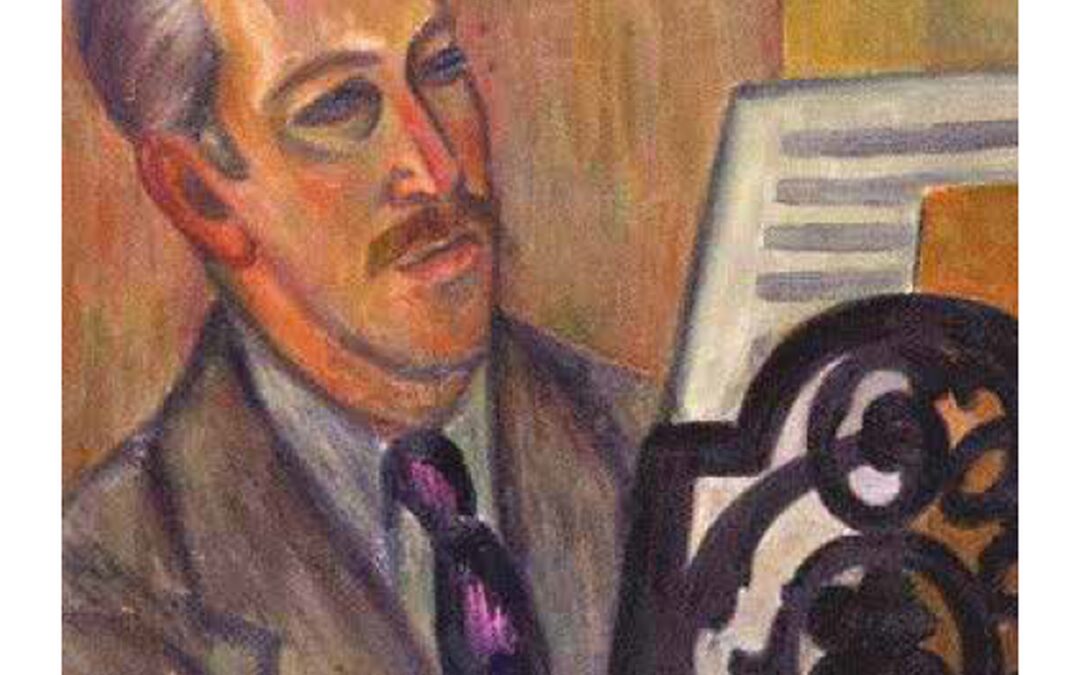

The brilliance of Spicer’s musical analysis and the career trajectory is not matched in drawing out familial or personal relationships. We are told that the Bliss family supported the writing of the book, but they appear in it too seldom. His younger daughter Karen helped with questions and saw some chapters before her death in 2021. One wishes that she had been able to contribute more; something to aid an understanding of what life in the Bliss household was like. Even the accompanying photographs are very short on family images, when just such images are needed. His long-lived wife Trudy should have a more prominent part in the book. Bliss dedicated his autobiography ‘To My Wife and Dear Companion during forty-five years’ but we never find out what made the marriage tick.

So, this is an efficient, classic, music biography, good on the professional aspects but not the private. There is no unpicking of the man who could write at the end of his autobiography that, if he were given the choice, he would choose not to be born again.

Review by Paul RW Jackson