Adam Pounds recalls three years of study with Lennox Berkeley

A young composer can often feel ‘lost’, and in 1976, while I was studying at the London College of Music and won the composition prize with my Oboe Quartet, I was sufficiently encouraged by this success to seek the help of a good teacher.

As a student from a modest and non-musical background I had no contacts amongst the musical establishment. My oboe teacher John Wolfe, who played in the BBC Symphony Orchestra, took some of my compositions to show the BBC Music Library and secured me some work as a music copyist. This brought me in direct contact with the new works of some contemporary composers from Alwyn to Birtwistle. I also worked for the jazz magazine Crescendo, and met some more commercially-minded composers, including Richard Rodney Bennett.

This was a period when Boulez and the avant-garde were at the height of their dominance of the musical scene. Although interested in their experiments, I clearly identified myself with the mainstream tradition of British music and the legacy of composers such as Vaughan Williams and Holst amongst others.

My partner Dinah, a flautist, was playing the Sonatina for Flute and Piano by Berkeley at this time. As neither of us was a proficient pianist, I transcribed the piano part for classical guitar, so that I could play along with her. Shortly afterwards I heard Berkeley’s Serenade for Strings on the radio. I was immediately struck by the inherent qualities of his music: its charm, its depth and, above all, its craftsmanship. This was a composer from whom I felt I could learn a great deal, if he had the time to teach me. Without further ado I wrote to him, enclosing my Oboe Quartet.

Eagerly I awaited a reply, but heard nothing for many months. I assumed he was much too busy. Or perhaps I was aiming too high. Then one morning a reply landed on the doormat. Sir Lennox was very courteous and apologetic – he had misplaced my letter and ‘it had only just come to light.’ To my delight he invited me to visit him at home in Warwick Avenue for ‘a little advice’.

I had lived, worked and studied in London all my young life but Little Venice was not a familiar area to me. I had tried to imagine what Lennox Berkeley and his house would be like. On arriving I was immediately impressed by the beautiful entrance porch. Sir Lennox himself answered the door, and invited me into the drawing room, where he invited me to sit in a comfortable armchair. I was struck by the lovely art work all around, and I felt comfortable and at ease. Sir Lennox had recently been knighted but I wasn’t aware, then, of his aristocratic background. From the first moment of our acquaintance he was always dignified, warm and a steadying influence.

I remember that first encounter clearly. Lennox wanted to know all about me. He asked what I played, what music I liked and what other interests I had. I felt he was really weighing me up. We moved to the piano, and he put my Oboe Quartet on the stand and complimented me on the elements he liked: the bold shapes and the rhythmic devices. He was interested in my composition process, and in how I conceived a work. I was waiting for the advice he had offered in his letter, but instead he put an early Mozart Symphony on the stand. He told me that a sound understanding of the classics was absolutely essential in forming a secure technique. Mozart, he believed, achieved the pinnacle of balance and economy in his style as well as elegance and refinement. Lennox’s advice was ‘write only the notes you need’. I listened intently while he explained the strengths of Mozart’s composition and orchestration.

This was a pattern he was to follow at every lesson. We only ever looked at a score whilst at the piano; we never listened to a recording. He evidently expected me to hear the orchestration in my head – as he could – even if I didn’t know the work. On one occasion I took a cassette recording of my Divertimento for String Orchestra, together with a cassette player, as I wasn’t sure if he had the means to play the tape. After searching for the correct electrical socket, we ended up listening to the piece downstairs in the kitchen.

At the end of my first encounter I was grateful he had taken so much trouble with me, especially as he claimed to have retired from teaching. ‘I think I would like to take you on’, he said gently, as I rose to go. ‘Let’s say once a fortnight.’

This was a very busy period for Lennox. He had started work on his Fourth Symphony, and he was busy with the composition of some vocal music. He had recently been elected President of the Performing Right Society and he was working with several prominent musicians on performances of his works.

We always began my lessons with a chat. ‘Auntie’ [the Berkeleys’ housekeeper Babs McKeever] brought us tea which he took with cream, which seemed very strange to me. The conversations would often stray beyond music. We discussed the merits of grammar schools versus comprehensive education, and on more than one occasion he seemed vaguely amused by my youthful left-wing opinions. Our lessons concluded with my paying a token fee, which he took almost reluctantly and with embarrassment, before pencilling the next lesson in his diary, and wishing me well in my endeavours.

During one memorable lesson he put his Flute Sonatina on the piano for analysis. In his characteristically modest way he explained how pleased he was with the first movement and the way in which he had brought the music back to the home key. I mentioned that this was one of Dinah’s favourite pieces and that it had been my first encounter with his music, whereupon his interest moved from music to me and Dinah. He asked how long we had been together. When I told him he said, ‘You know, marriage is a very good thing. Perhaps you should consider it.’ I’m sure he would be pleased to know we have just celebrated our thirtieth wedding anniversary.

Whenever I arrived at Warwick Avenue for a lesson Lennox’s wife Freda would greet me with a friendly welcome. ‘Lennox will be with you shortly’, she used to say. As he entered the room I often felt his attire reflected his mood. Sometimes he would appear formally dressed in a blazer with a handkerchief and tie, and his manner would be correspondingly formal. At other times he was casually dressed – and more relaxed in his approach.

At each lesson he would set aside a little time to study a new score, usually by Bach or Mozart, just as Nadia Boulanger had insisted he and his fellow students in Paris should do. Sometimes he would use his own work to illuminate a particular technique. We looked at his Chinese Songs and the Oboe Sonatina in detail. Those familiar with the latter work will know that the first movement begins with a note-row. In my lesson he explained how he could have extended this technique for the whole piece if he had been following serialism faithfully, but he was quite dismissive of the method. It had served its purpose as an introduction in the sonatina, but then he had reverted to his own idiomatic style.

The lessons provided me with a tremendous stimulus. I was constantly writing and taking work for him to look at, trying out new ideas. I always sat to Lennox’s left at the piano and played the bass line of the scores while he played the upper parts – often clenching a pencil in his teeth, ready for corrections.

Although he was invariably encouraging, he found some of my work too aggressive. On more than one occasion he suggested changes – usually harmonic, since he considered some of my chords rather harsh. Only once or twice I resisted his moderating influence. He rarely dwelt on the emotional impact of the music, but focused instead on the technique. However, during my period of development as a student with him I achieved a clarity of orchestration which was in marked contrast to the heavily-scored textures I had used in my earlier works, and without doubt his influence has continued to encourage lightness and purpose in my compositions. I recently looked at the corrections he made in my scores during 1976 and noted that these showed a practical concern for the performers as well as for the construction of the music.

Lennox rarely talked about himself. When he referred to other musicians with whom he was working, he always spoke with high regard. He never mentioned his associations with Ravel, Poulenc or Britten. I only learnt of these much later. When Britten died in 1976 it was the only time Lennox spoke of him, explaining to me about Britten’s long illness. Later I watched Lennox pay a tribute to Britten on ITN News.

During the period of my last few lessons in 1979, Lennox had started work on his last opera, Faldon Park. On one occasion he looked exhausted. Like Britten, he was extremely industrious, and self-critical.

When I went to the unveiling of the blue plaque at 8 Warwick Avenue last year I realised that nearly thirty years had passed since my last lesson there. I remember clearly his parting advice, ‘Try and write with performers in mind. Get your music played as often as you can by as many people as you can – this is the most important thing.’ He said he thought he had helped me to the best of his ability, ‘but come back and see me if you need any more help. I’d like to think of you as a friend’.

Teaching composition is one of the most problematic areas of music education, and I have always considered Lennox to have been an excellent teacher, as well as a very fine composer. He was blessed with the ability to encourage and enthuse. On the occasions when we may have had a difference of opinion, he always left me reflecting on my work, and this is surely paramount in a composition teacher.

Written in April 2010; article reproduced with the kind permission of the Lennox Berkeley Society.

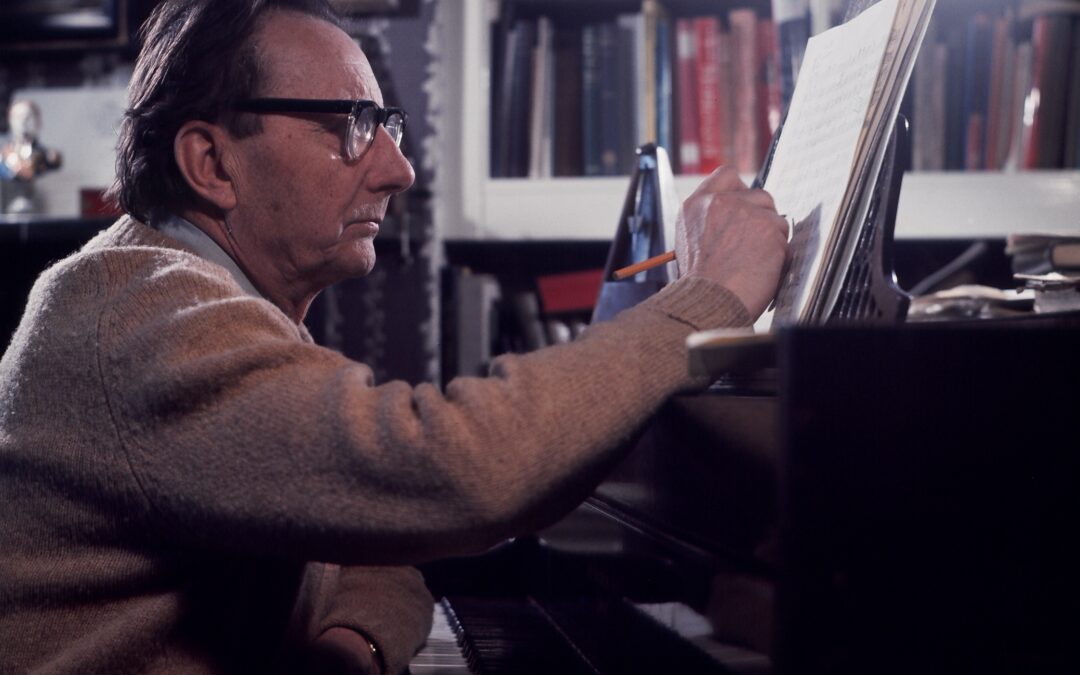

Photo credit: Sir Lennox Berkeley, in his study at Warwick Avenue, London, in 1973 (Photograph Godfrey MacDomnic, by permission The Lennox Berkeley Society)