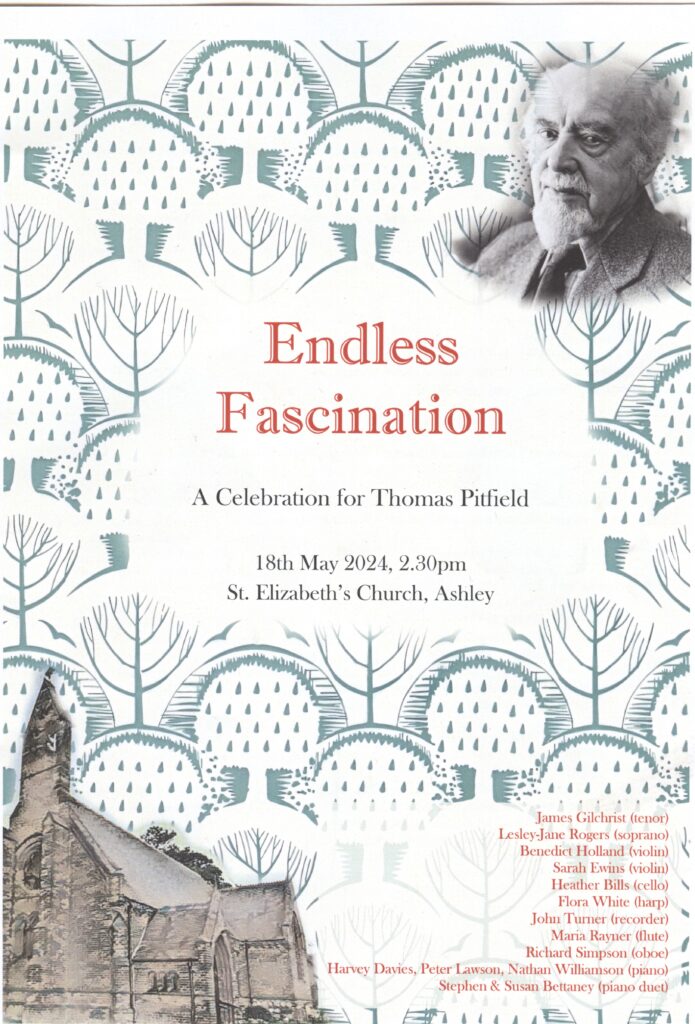

St Elizabeth’s Church, Ashley, near Altrincham

18 May 2024

Thomas Pitfield (1903-99) can best be described as a 20th century Renaissance man. Although primarily known as a composer, he was also a prodigious artist, poet, engraver and cabinet-maker. He taught composition at the Royal Manchester College of Music (which later merged with the Northern School of Music to become the Royal Northern College of Music) between 1947 and 1973, where his students included John McCabe, Ronald Stevenson and John Ogdon.

Endless Fascination provided a timely opportunity to review his musical achievement. The event was something of a marathon, presenting a generous variety of his chamber works alongside a number of miniatures composed in tribute to him by ex-students (David Ellis, Philip Spratley and Max Paddison), colleagues and admirers. It doubled as a book launch for Endless Fascination, Forsyth’s recently published lavish volume of autobiographical writings and critical essays, edited by Rosemary Firman and John Turner.

Jeremy Dibble and Rosemary Firman introduced the man and his music, and the concert that followed included works composed between 1931 and 1973. The piano, an instrument for which Pitfield clearly had a special affinity, figured quite prominently throughout, and indeed no fewer than five pianists were called upon to share playing duties.

Pitfield shunned the large-scale Germanic symphonic works of the late Romantic period and favoured brevity and economy in his own music, which tended to be influenced rather by French and English repertoire. The 1931 piano work, Prelude Minuet and Reel, carries echoes of Ravel’s Sonatine, while Minors: Dance Suite of 1965 is reminiscent of Warlock’s Capriol Suite, but with a playful, acerbic manner that is Pitfield’s own. His predilection for 7/8 metre is a characteristic eccentricity indicative of something more mischievous, if not downright sinister, that lies under the surface of his music.

Many of the other pieces heard here adopt an easy-going neoclassicism owing something to the example of Poulenc, and like him, Pitfield tends to place the emotional weight in his slow movements, always containing it within highly wrought structures. With the Sonatina for harp, deftly played by Flora White, a more overtly sensual side of Pitfield’s composing was revealed, a direct and affecting delight in sonority for its own sake.

James Gilchrist, accompanied with great sensitivity and imagination by Nathan Williamson, presented two groups of Pitfield’s songs (recently recorded by them). Many of them were set to words written by the composer himself (originally an expedient he adopted when the copyrights on preferred poems proved prohibitively expensive, a practice shared by Charles Ives!). Pitfield’s songs are beautifully crafted, embodying his ideals of directness and economy. Readily identifiable as being rooted in the English tradition of Finzi and Vaughan Williams, they encompass a wide range of emotions, from wistful or nostalgic to folky and earthy. The extraordinary Skeleton Bride – a recitation with piano – stood out as being unusually quirky and sinister. Like Ravel, Pitfield does have a tendency to delve into darker regions from time to time!

Most of the short pieces composed in tribute to Thomas Pitfield were specially written for the occasion, although two older works were also included. Gordon Crosse’s gorgeous Lullaby was an 80th birthday tribute, while Old Willows by David Ellis was composed in 2000 in memoriam. It is a substantial study in piano resonance, making intriguing use of piquant harmonies and recessed textures. Powerfully advocated by Peter Lawson, it made a memorable impression.

The new works deployed an ensemble of soprano, recorder and harp, with the ever-reliable Lesley-Jane Rogers joining John Turner and Flora White. Such an intimate combination of voice and instruments invites the use of gentle, open textures, and many of the pieces were bucolic rather than overtly dramatic in expression. Wendy Hiscocks, John Alexander, Peter Rose and Robin Nelson all contributed attractive and characterful compositions in this vein.

Among the more outgoing pieces, Philip Spratley’s Beauty was very finely paced and crafted, building to a telling emotional climax, and Elis Pehkonen’s The ticking room introduced the sounds of a metronome to create a troubled, unnerving atmosphere. The most overtly operatic of these works was Adam Johnson’s The migrants, effectively a short dramatic scena. With the addition of Richard Simpson’s oboe to the ensemble, the textures aspired towards orchestral intensity.

There were settings of Pitfield’s own words by John LeGrove, Sasha Johnson Manning and Nicholas Marshall, and Adam Gorb in A composer’s day opted for a particularly waspish and possibly autobiographical text.Three short instrumental works by Max Paddison, Peter Hope and Martin Ellerby completed the collection of tributes.

The concert as an entity was very well planned and beautifully executed. However, it must be admitted that the chamber works alone do not provide a fully rounded picture of Pitfield’s achievement. It is worth exploring his First Piano Concerto for evidence of what he could do when allowed a larger canvas to work upon.

Review by George T Nicholson