Born in Bolton in 1903, Thomas Pitfield was an almost exact contemporary of his fellow Lancastrian, William Walton. But he enjoyed none of the remarkable luck that saw Walton translated from Oldham to Oxford, and ultimately to an island in the Bay of Naples where he basked in international acclaim. Moreover, unlike Walton’s parents, Pitfield’s were not musical. Nonplussed by his artistic leanings, they did what they could to discourage him from pursuing a career in music, and when at the age of 14 he left school he deferred to their wishes by commencing a seven-year apprenticeship with a local engineering firm.

In his spare time, however, he studied music and had piano and harmony lessons with the organist of Bolton Parish Church. He acquired fluency on both the piano and the cello, and although organ lessons had to be abandoned through lack of funds, he nonetheless acquired enough ability to play for services with enough knowledge of the instrument to write for it. He also then started to compose for local events.

In 1923, Pitfield abandoned engineering, made what he himself described as a ‘Declaration of Independence’, and entered the Royal Manchester College of Music. Here he studied composition with Thomas Keighley and cello with Carl Fuchs (principal cellist of the Hallé Orchestra). But financial difficulties obliged him to abandon his studies after a year, and those composition lessons with Keighley were the only ones he ever received. Undaunted by an unsuccessful application for an RCM scholarship, he began a private teaching practice, busied himself with music-making at a local level, and became a church organist.

In 1926 he founded a string quartet and continued to compose. Some of his works were performed. These activities necessarily took place while he was still living with his parents, an arrangement rendered particularly unsatisfactory by his poor relationship with his mother. This never improved and even worsened in 1928 when his father died.

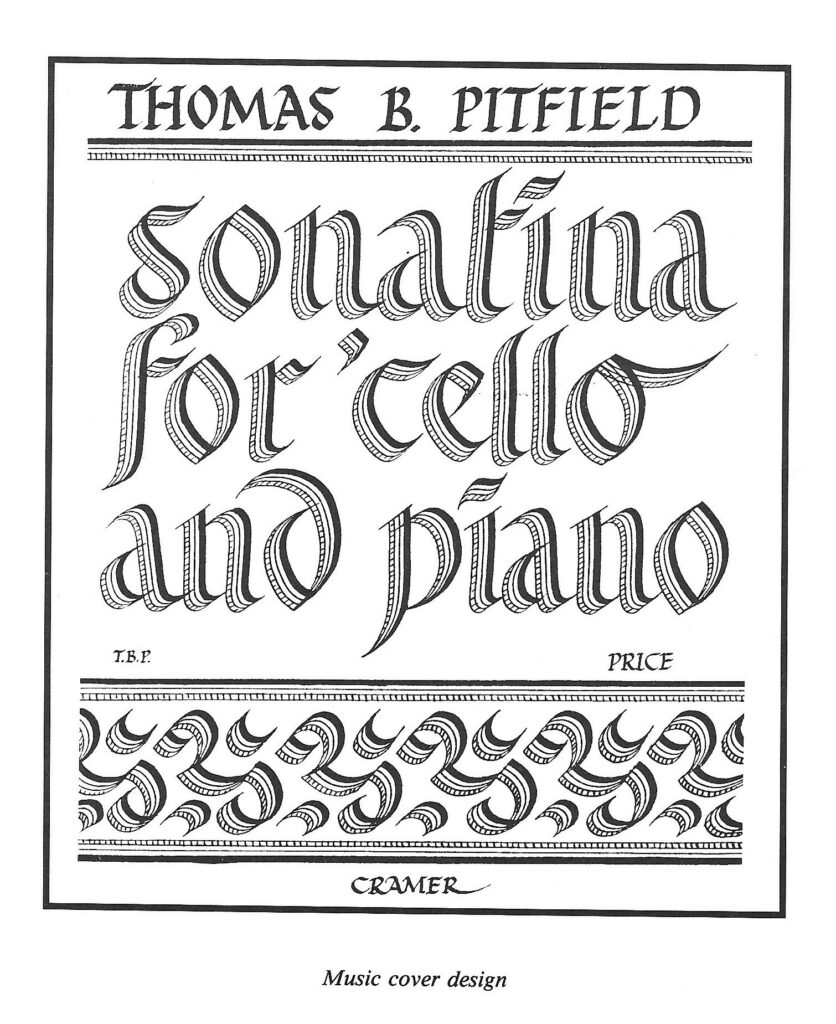

Doggedly, he pressed on and a Wordsworth setting for male voices, She dwelt among the untrodden ways, was published in 1929. The early 1930s saw further publications. He also formed a close friendship with Hubert Foss of Oxford University Press. One result of this was an invitation to design covers for a number of scores, including in particular that of Britten’s Simple Symphony.

Another outcome was the publication by OUP of his Prelude, Minuet and Reel, a work dating from 1931. Having in due course decided to re-train, Pitfield won a scholarship to study art and cabinet making at the Bolton School of Art, and in 1935, having completed his studies, he acquired a teaching post at Tettenhall College that involved handicraft, art and – from 1940 – music.

The same year, 1935, saw not only his marriage to Alice but also the BBC’s first broadcast of his music with a performance of some songs. Such broadcasts continued, although Pitfield’s relationship with the BBC was not an entirely happy one. In the 1960s in particular, there was resistance to his music from some of the corporation’s staff.

In 1939, Pitfield settled in Wolverhampton, where, as a teacher and a conscientious objector, he was exempted from military service and spent much of the war promoting pacifism. In 1945 there began a fifteen-year period that constituted the high-water mark of his musical creativity, and he received that year an invitation to teach at the RMCM. It was rescinded, however, partly it seems in response to pressure from Richard Hall, who taught Birtwistle, Maxwell Davies and other composers of the avant-garde.

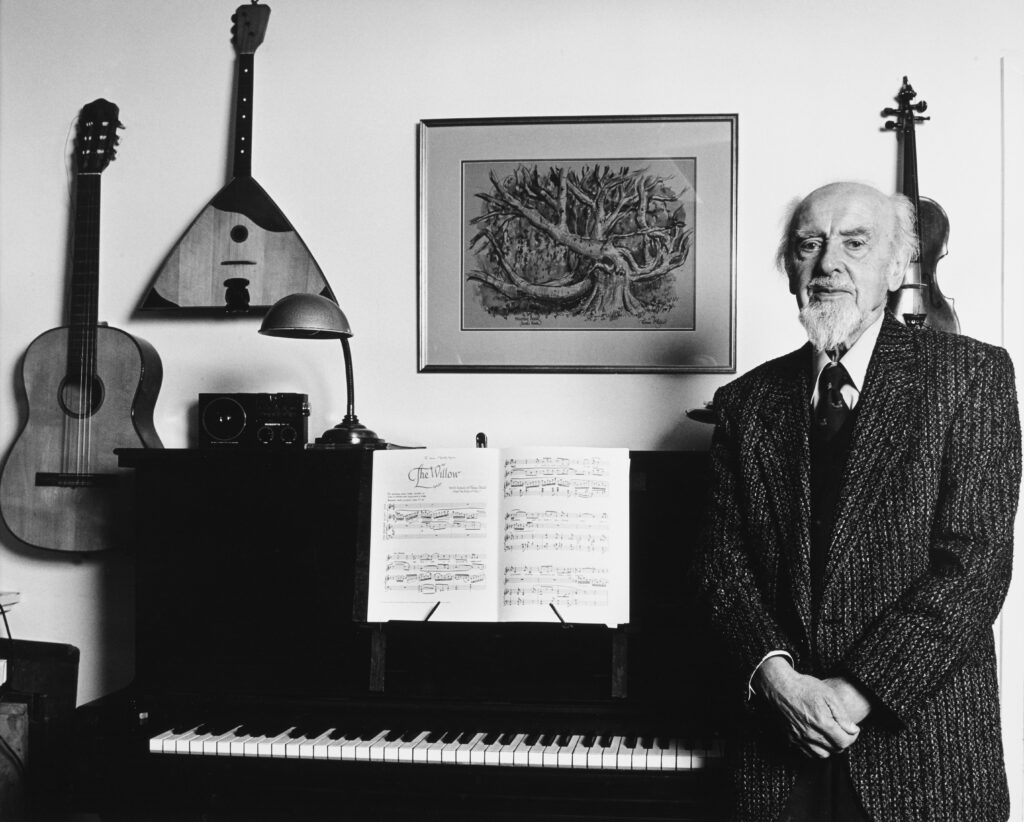

Having given notice to Tettenhall College on the strength of the invitation, Pitfield found himself without a job; but in 1947, after two years’ freelance work, which included some examining for the Associated Board, the invitation was re-issued. Having accepted it, Pitfield moved to Macclesfield and began teaching at the RMCM one day a week, and he remained on its staff until his retirement. In 1957, he and his wife settled in Bowdon, a suburb of Altrincham, where with money from Alice’s family they were able to build a home designed and decorated by Pitfield himself. He remained at Bowdon for the rest of his life. Thomas Pitfield retired in 1973, and his seventieth birthday was marked by a BBC broadcast. He continued to compose and died in 1999.

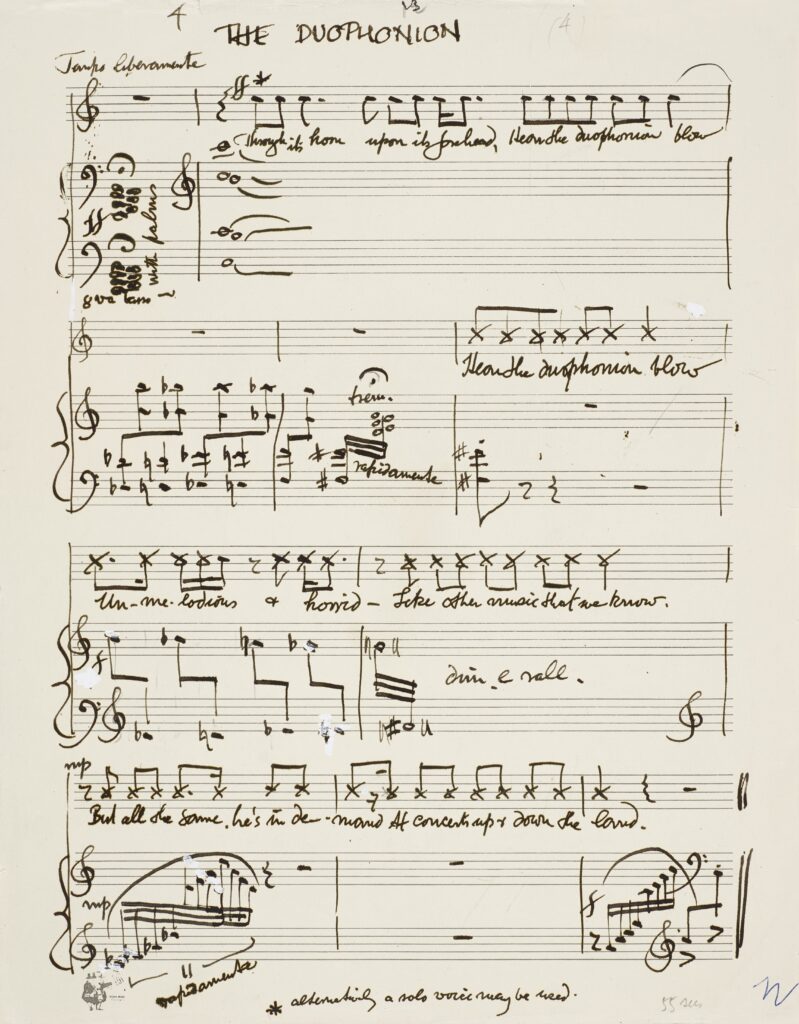

In his will, Pitfield described himself as ‘Composer, Artist and Author’, which usefully clarifies how he thought of himself. John Turner goes further by describing him as a ‘composer, artist, author, poet, designer, craftsman, woodcarver, calligrapher, vegetarian, pacifist (and very much more)’. Clearly, though, composition came first, and here he was essentially a miniaturist, taking the view that it is ‘better to build small, firm bridges over native streams than try to build uncertain ones over the wide seas.’ He did however compose a number of large-scale works, including two piano concertos, and any temptation to draw negative inferences from the relative obscurity the music currently enjoys is necessarily checked by the knowledge that musicians of the stature of John Barbirolli and John McCabe championed and performed it.

In Forsyth’s excellent publication: Endless Fascination: the life and work of Thomas Pitfield, composer, artist, craftsman, poet the editors Rosemary Firman and John Turner follow the book’s title by adopting the sensible practice of describing the life and the works separately. Parts 1 and 2 deal respectively with ‘Life’ and ‘Work’, and rather than attempt a biography themselves, or commission a third party to undertake the task, the editors have incorporated three of Pitfield’s autobiographies, viz., No Song, no Supper, which was brought out by Thames Publishing in 1986, A Song after Supper (Thames Publishing, 1990), and Honeymoon: incidents from a sixty-year holiday diary (Kall Kwik of Altrincham, 1998). We therefore have Pitfield’s life in his own words (a fourth autobiography, A Cotton Town Boyhood, was published in 1995).

Part 2, the section dealing with the works, is necessarily the longest, given the impressive range of Pitfield’s interests and skills. Jeremy Dibble deals with the music, at length and in considerable detail; Stephen Whittle writes about Pitfield as artist and craftsman; Dr Firman covers the books and the poetry; and Stuart Scott reflects on Pitfield and the Arts and Crafts Movement. Frederik Van Dam and Ghidy de Koning write about the use of wood in Pitfield’s The Poetry of Trees, which dates from 1942; John Turner offers an account of Pitfield as pacifist; and Part 2 concludes with a gallery of drawings, linocuts, watercolours, etc. compiled by Michael Pollard.

Part 3 comprises a sequence of memoirs by, for example, Norma Pitfield, his niece; a colleague from his Tettenhall days; and ex-pupils such as John McCabe and Professor Max Paddison.

In Part 4, John Turner provides not only a list of the many compositions that make up Pitfield’s huge output but also a discography; and Stuart Scott contributes to this section a chronology of BBC broadcasts of the music.

The fifth and final section of the book reproduces the sleeve-notes that accompanied Flying Kites: a Trafford Miscellany, a 2005 recording of music by Pitfield and various friends and acquaintances. It includes the xylophone sonata and a number of works in which the broadcaster Richard Baker, a friend of Pitfield’s, takes part as reciter. A compact disc of the recording accompanies the book (a bonus indeed).

Does any significance attach to the fact that Pitfield put ‘Author’ last? Those coming to the autobiographies for the first time, and having no first-hand knowledge of the man, may feel that his prose is not exactly his best advocate. This is partly because of the manner of his writing and its general tone. In this connection, the editors’ phrase ‘protracted earnestness’ is spot-on. Allowances must of course be made for an author from a generation now extinct, and such things as ‘aforementioned’ and ‘bestir’ can be passed over easily enough, as can his fondness (which becomes a mannerism) for beginning clauses with ‘for’, which imparts a quasi-biblical flavour.

But it is what Pitfield has to say in his autobiographies, not merely the manner of his saying it, that is sometimes disturbing. It is very much a case of Pitfield contra mundum. There is much grumbling and much criticism of others, and at such times he can seem chippy and resentful, as when he refers to public-school masters (or blames the RMCM for his ignorance of its Patron’s Fund).

No one would want to play down the difficulties he had to contend with. The incomprehension of his parents was merely the start. He endured poverty, poor accommodation, unhelpful employers, unhelpful landlords and prejudice at the BBC. He sometimes led a precarious existence, and it took him many years and many struggles to find a niche in which he could express himself artistically, be true to his ideals, and enjoy reasonable financial security (and it was not until he reached the age of 70 that he started to enjoy that security). But some readers may reach a point at which they yearn for the other side of the story and conclude that there were times when Pitfield may have done himself no favours. Perhaps, like so many sensitive people, he failed to appreciate that others could be equally sensitive, that others could also be wrestling with difficulties.

Yet Part 3 of the book is eloquent of a warm and engaging personality, the limericks and nonsense rhymes demonstrate that he was capable of coming down from the mountain top, and his large output is clearly that of a man who applied himself to his work with extraordinary energy, commitment and integrity. It was undoubtedly a life well spent.

The editors have performed their task with flair, imagination and precision. It has clearly been a labour of love, and the book itself is a joy to engage with. The paper is of high quality, the pages are sewn and not glued, the many and varied illustrations have emerged clearly and unscathed from the printing process (except the musical illustrations on page 358, which are a little indistinct), and the ribbon bookmark is a delightful touch.

This book is a very handsome tribute to a fascinating but little-known figure. It can be recommended without reservation to all devotees of English music, not only for what it says about Pitfield but also for its insights into what it meant in his day, to be a composer without the benefits that flowed from attendance at a public school, Oxbridge and the RCM (and without the benefit of such things as Walton’s extraordinary good fortune and Vaughan Williams’s silver spoon).

Written by Dr Relf Clark

Rosemary Firman and John Turner, eds

Endless Fascination [:] the life and work of Thomas Pitfield, composer, artist, craftsman, poet

Manchester: Forsyth Brothers Limited, 2024

540 pages, ISBN 978-0-9514795-4-4, £40

Images supplied by Michael Pollard and Simon Paterson