26 May 1926 – 9 February 2022

I met Joseph Horovitz, who died in February at the age of 95, more than 25 years ago. Arriving at his west London villa to interview him for an article, I was writing about his ballet music. I was immediately struck by his voice; his English, even 50 years after leaving Vienna, had a wonderful musical lilt to it. His manners too seemed to belong to a more gracious era. He was utterly charming, with a formidable name for people and places, and full of stories and I am pleased that we maintained a friendship over the years. As composer, pianist, conductor, and teacher Joe’s influence on British music was vast. Even if some may not recognise the name, most would recognise some of the music.

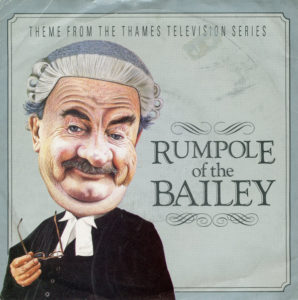

Joe (pictured above; photo credit Wolfgang Jud from Wise Music) was born into a cultured middle-class family in Vienna, the son of Lotte Horovitz and her husband Béla, cofounder of the Phaidon Press. After a difficult escape from the city, only two days after the Anschluss the family settled briefly in London, where he attended Regents Park School for refugee children, but moved to Oxford during the Blitz. He was educated at the City of Oxford High School, where he developed ideas of being an artist and took lessons at the Ruskin school of Drawing based at the Ashmolean. His musical talent eventually won through and in 1943 he began to read Modern Languages at New College, Oxford, alongside this he studied with Egon Wellesz, also from Vienna.

On graduating in 1948 he went on to study composition at the Royal College of Music with Gordon Jacob as his main teacher. There he won the Farrar Prize for his first ballet score The Emperors Clothes though he recalled ‘I never heard it, no one ever played music that won prizes’. By selling some of his portraits he paid for a year’s study in France with the redoubtable Nadia Boulanger who “taught me to admire, to emulate, sometimes even to imitate the procedures of Stravinsky in his neoclassic manner”. This neo-classical edge with a hint of Vaughan Williams and Viennese romanticism are corner stones of his work. He also loved jazz and several of his works have a jazzy edge to them. However, the jazz was notated, and he hated performers trying to add extra swing.

Returning to Britain his many facetted career quickly took off. He took up a post as music director of the Bristol Old Vic, composing, arranging, and performing incidental music for two seasons. His conducting career took off when he was invited by Arthur Benjamin to be assistant conductor for the Festival of Britain open air performances of his ballet Orlando’s Silver Wedding, “Arthur was so good to me” he recalled. He became conductor for the Original Ballet Russes and worked as assistant to Antony Hopkins at the Intimate Opera Company. His first compositional success was in ballet (he would write 16 in total) in 1951 with Les Femmes D’Algers and in 1953 Alice in Wonderland both for London Festival Ballet.

In 1961 he began his long teaching career at the Royal College of Music, where his dogma free teaching, insatiable curiosity, and interest in all things musical, were much appreciated. Over the years many of his students had musical sympathies very different to his own but he always endeavoured to help them find their own path. This busy, varied, schedule continued for the rest of his life.

He was sufficiently well known by the late 50s for Gerard Hoffnung to ask him to write for his humorous musical concerts, including the hilarious Metamorphosis on Bedtime Themes and the Horrortorio. He was regularly commissioned for a range of scores from chamber to orchestral to brass band. He was somewhat frustrated that his orchestral music was not performed more often while music by less talented composers was. But his melodious style of orchestral writing was not fashionable in the 60s and 70s. He told me, and in this he was in tune with Malcolm Arnold, “I want to write music that I would like to hear, but which nobody has written”.

Although I have said he had a sparkle about him there was also imperceptibly a touch of sadness or regret. Usually kept in check it surfaces in the String Quartet No 5 written to mark the 60th birthday in 1969 of the art historian Sir Ernst Gombrich and given its premiere by the Amadeus Quartet. Realising that he, the dedicatee, and the players had all suffered because of the Nazis he included in the work, to chilling effect, a twisted version of the Nazi anthem the Horst Wessel Lied. As he said, “You cannot have the experience of being ejected from your home without remaining intensely uneasy.” It is telling that he said that if only one of his works had to be saved he would choose this quartet.

His largest work, a three-act opera Ninotchka, based on the MGM film starring Greta Garbo has yet to be performed. He completed it in 2006 and I will never forget a memorable afternoon when he invited me over and he played, very well, and sang, very badly, the whole score. It is an idiomatic work that fully catches the charm of the story and the period. Although he never got round to orchestrating it, it would be a rewarding work for both performers and audience alike.

His work with ballet proved he could work to fixed timings and he was soon taken up by television producers as a sure bet for theme and incidental music, (there is even music for a Tarzan film). Of the genre he observed that “You’ve got to be able to write to order and to time. You also have to have an adaptability. You have to be able to catch the flavour, the period, the custom, everything to do with what the film is about.” This he did perfectly for many Agatha Christie adaptations, but his most popular work in this genre was for ITV’s Lillie and Rumpole of the Bailey, the latter of which he was very proud.

He was the most affable of men but in musical matters, especially concerning his own works, he expected things to be right. He was very pleased when his Jazz Harpsichord Concerto was played at the 2021 Proms, and although Covid restrictions stopped him from attending he listened on the radio. He was furious with the ensemble for, without any consultation, they inserted two overblown improvised solos for double bass and then drum kit. These destroyed the proportions of the work and thus his perfectly conceived work.

Fortunately, over the years he recorded much of his music and so we can hear just how the composer wanted his works to sound. Of note is an ASV cd which included his Oboe Concerto and Sinfonietta in its orchestral rather than brass band version. Clarity of texture, attention to detail and a warm sound leap out. It would be wonderful if John Wilson, a former student, of whom he was very proud, could find time to record some of his old teacher’s music.

His 90th birthday was celebrated on Radio 4 by a documentary No Ordinary Joe presented by Debbie Wiseman and from which I have stolen the title. In it he said, “If people find, for instance, three minutes of a piece of music of mine which they’d like to hear again, that’s a wonderful thing”.

Joe had a long association with the BMS and in 2017 he gave a lively talk to members to coincide with the release of the society’s recording of some of his songs.

His death has left an unfillable gap in British musical life, they don’t make musicians like him anymore. But his life enhancing musical legacy lives on, to quote from his first major success Alice in Wonderland, like ‘a memory of a summer day’.

In 1955 while coaching at Glyndebourne he met the journalist Anna Landau. On an early date he took her for a drink at the very popular musicians club the International Music Association in South Audley Street. He was horrified to see Malcolm Arnold, a friend but one with an eye for the ladies approaching. On this occasion Arnold was at his most charming and said, ‘hold on to her Joe, you’ve got a good one there’. Happily, he followed Arnold’s advice and the two were married in 1956. She survives him as do his children and grandchildren.

Obituary by Paul RW Jackson

Related article: BMS tribute to Joseph Horovitz